By Hassan Keynan

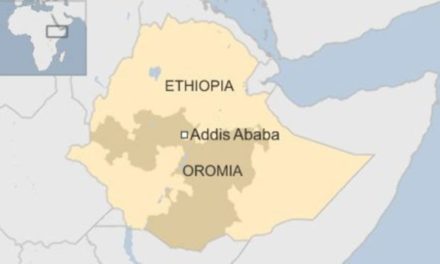

9 September 2020 marks a critical milestone in modern Ethiopian politics. For months Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has used and manipulated both chambers of the Parliament, the judiciary, and the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) to warn Tigray against going ahead with its planned elections. Addis Ababa insisted that any elections held in Tigray would be illegal and unconstitutional, and therefore null and void. The Federal Government even made it clear that it would not hesitate to blockade Tigray and impose severe punitive measures on it.

However, on the morning of 9 September 2020 Tigray finally called PM Abiy Ahmed’s bluff, keeping the promise to hold elections in defiance of the threats and ultimatums emanating from the executive and legislative branches of Federal Government. Reports from Tigray indicate the polls for the 190-seat regional parliament were held in an environment that was peaceful, orderly, and relatively COVID-19-safe. Close to 90 percent of the nearly 3 million registered voters cast their ballots in 2600 polling stations. Unable to stop the elections in Tigray, PM Abiy Ahmed’s administration resorted to desperate measures aimed at preventing journalists and observers from traveling to Tigray for the purpose of reporting on the elections or monitoring them. The final results are expected on 13 September at the latest.

Tigray’s well-organized and successful elections mean a great deal more than a mere electoral event. At the heart of the matter is a constitutional crisis that engulfed the country when the incumbent administration indefinitely postponed the federal elections scheduled in August this year, citing reasons related to COVID-19. The unilateral fashion and the speed with which the Prime Minister and his Prosperity Party (PP) framed and managed the case for postponing elections raised legitimate concerns that the tyrannical instincts and the authoritarian demons that have convulsed the Ethiopian state since its inception might be rearing their ugly heads. What particularly irked most people and alienated many was Abiy Ahmed’s creepy flirtation with openly and unashamedly anti-federalist forces hell-bent on rolling back and ultimately getting rid of the ideas, principles, and institutions of federalism that inform and underpin the current constitution. There was widespread fear that Prime Minister Ahmed and his Prosperity Party (PP) were using and exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic to stay in power beyond their constitutionally mandated five-year term limit.

Although this was a corrosive anxiety that has swept across the country, not all the constituent regions and autonomous city administrations of the federation were able or willing to openly confront the PP juggernaut led by its mercurial Nobel Peace Laureate. The bulk of the burden appears to have fallen, not unexpectedly, on the shoulders of the two core regions of the Ethiopia.

Oromia on fire

When he saw that the opposition to PP’s unconstitutional grab for power was gaining strength and momentum, the Prime Minister decided to wage a war on the most formidable opponents in Oromia, the undisputed heavy weight in the country in terms of territory, demography, politics, and economy. He struck first and hardest those closest to him. Following the assassination of Haacaalu Hundeessaa, a popular Oromo artist, activist, and icon, by unknown assailants in Addis Ababa on 29 June 2020, the Prime Minister rounded up all senior Oromo opposition politicians, threw them in jail, or put them under house arrest. Leaders and supporters of the two leading opposition parties, Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), have been particularly targeted. These included Jawar Mohamed who is credited to have spearheaded the popular uprising that toppled the previous regime and brought Abiy Ahmed to power, and Lemma Megersa, former President of Oromia and former defense minister. Abiy Ahmed followed up on this with a savage counter insurgency campaign across large swathes of Oromia in an effort to wipe out all signs of opposition to his rule in Oromia. This campaign of terror was conducted in a shroud of secrecy coupled with a complete shutdown of the internet and private media outlets. Abiy’s Rose Terror in Oromia was modelled on the Crimson Terror that was experimented and perfected in the Ogaden, particularly during the ten years between 2007 and 2017. Although Abiy Ahmed’s administration has set Oromia on fire, the reckless and indiscriminate violence has so far failed to root out opposition in Oromia. In fact, it appears to have backfired as the youth-led popular uprising and economic boycott campaigns continue unabated across much of Oromia, with far-reaching consequences for the political and economic stability of the country.

Tigray on the path to separation

However, it is in Tigray that Abiy Ahmed has found his strongest, most determined, and most vocal opposition. There are many reasons for this. First, Tigray is the birth place and most enduring stronghold of the historical Abyssinian state, the entity that had informed the creation and evolutionary trajectory of modern Ethiopia. Second, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) had spearheaded the armed rebellion that toppled the military junta led by Mengistu Hailemariam in 1991 and dominated politics in Ethiopia the following 27 years. Third, Abiy Ahmed has joined forces with Tigray’s historical political rival and arch foe, the Amhara, to discredit the achievements and legacy of the TPLF-dominated EPRDF government, including the formulation and adoption of the current Constitution and ethnic-based federalism. Fourth, Tigray has the capability and the motivation to directly and effectively challenge Addis Ababa on multiple fronts, including a military option should it come to that. Tigray’s geographical location and the wealth of experiences and assets it has accumulated over the past 27 years constitute additional advantages that no any other region has. Abiy Ahmed’s reluctance to use military and other extreme punitive measures to stop Tigray from holding elections has little to do with enlightened leadership, devotion to lofty ideals, or profound belief in God or country on the part of the Prime Minister. It has a lot to do with a deep concern, even fear, about the outcome of any form of hostile intervention in Tigray. Fear of a protracted and costly conflict with Tigray and fear resulting from the humiliation of losing power weighs heavily on the mind of the Prime Minister.

The Center can no longer hold

With Oromia on fire and Tigray almost divorced from the center and on the path to separation, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed faces a situation that no any other Ethiopia leader had faced. Will the political fiction imagined by Menelik 129 years ago remain united and stable? Can Ethiopia continue to exist without its foundational and ancestral dominion and its demographic and economic stronghold in constant turmoil? These are the questions that torment the self-anointed 7th King of Ethiopia. The 2019 Nobel Peace Prize sits alone, isolated, and unhinged in the Imperial Place in Addis Ababa built by and named after his role model, Menelik, which he renovated at a cost of $170 million with the help of Indian experts flown from Gujrat and Punjab. Consumed by the anxiety and fear of presiding over the end of the of the Ethiopian empire, Abiy Ahmed spends his days routinely thumping the panic button. And the dominion over which he rules remains a dominion with no center nor savior.

Hassan Keynan is a former Professor and a senior retired UN official who worked in Africa, Asia and Europe.